“The experience of discovery is increasingly rare in our homogenized and airbrushed world.”

—DJ reading a promo for my local radio station

On a road trip a month ago, I stumbled upon a place that I don’t know if I should tell you about.

O.K., I’ll go on, but I’ll keep the exact location secret.

It’s not that it’s some Mafia hideout or portal to Hades or something. Let me explain.

Somewhere in the woods of the Door Peninsula of Wisconsin, Google Maps was not taking me where I wanted to go. The sky was bleak and windy, and the forecast warned of a storm, so I was thinking of heading back to Milwaukee. I hunted for a place to pull over and turn around. There were signs saying “Lighthouse ahead. Fee required.” What was it talking about? I pulled over in a parking lot, and that’s where I found it:

On the pebble-covered beach, a sign said, “Tractor only.” Beyond, a pine-cloaked isle sat in Lake Michigan, connected by sandbar shallow enough to wade across. After a few minutes, a tractor drove through the waves and ferried several of us tourists to [redacted] Island. The speck of land’s sole developments consisted of a one-room museum, a handful of historic buildings, and a still-active 19th-century lighthouse. The wagon had a life preserver strapped to the side. I wondered whether it was required to have one — like it was legally classified as a boat — or if it was just for show.

I thought this maritime tractor ride was an unusual find, so I considered pitching an article about this to a travel site. But then I thought: A big part of what I liked about this place was not that I couldn’t have found about it online (I could have) but that I didn’t — that I stumbled on it. And yet, if I spread the word, it will make it less likely that people will find it by themselves.1

One of the best things about traveling is exploration. Getting to know a place in ways that you can’t from a guidebook. Finding things that you didn’t have knowledge of.

It’s going to a certain park in Minneapolis and discovering, oh, there’s women selling mangoes with Tajin spice and oh, the path to the waterfall is fenced off, but the locals treat the “do not enter” signs with a real sign-not-a-cop attitude, so I’ll hop the fence too.

It’s going to a random beach in Milwaukee and noticing that the pebbles are smoothed remnants of the dilapidated piers jutting from the shore, still containing rusty segments of rebar.

It’s thinking “Wow I didn’t expect the river to be so wide. What is this, Lake Pontchartrain?” when you drive across the Arkansas River at Little Rock or the St. Croix at Hudson, WI, or the Mississippi at Keokuk or… you get the picture: I get impressed at the width of rivers.

These details may be mundane, but sometimes the things that you stumble on spontaneously are better simply because that’s how you came across them. You didn’t look them up and plan them out.

I sound like I’m writing a travel ad here, but I’m not just being sappy. If I had read about that island online, I don’t know that I would have chosen to go to it.

My thought is: Are tourism websites and the Internet in general destroying people’s opportunities to discover things?

As technology has advanced, information about the world has become more comprehensive and easier to access. If you project this trend into the future, every place a traveler could want to see will become known in advance. Any obscure place will be scoped out and made well-known.

True, this will not eliminate all the value in seeing new things. Even if you know about something in advance, you can still enjoy it.

But the ability to spontaneously discover things will dry up. Any trip will become like a movie that you’ve had spoiled, or one that you have seen so many times you have it memorized. Of course, scientists insist spoilers do not ruin a movie — as if that is something that can be evaluated scientifically yet. But although familiar experiences are valuable in their own right, new and unpredictable experiences are also worth preserving. And it is not clear that they will be.

I want to get my tips from random locals, damn it.

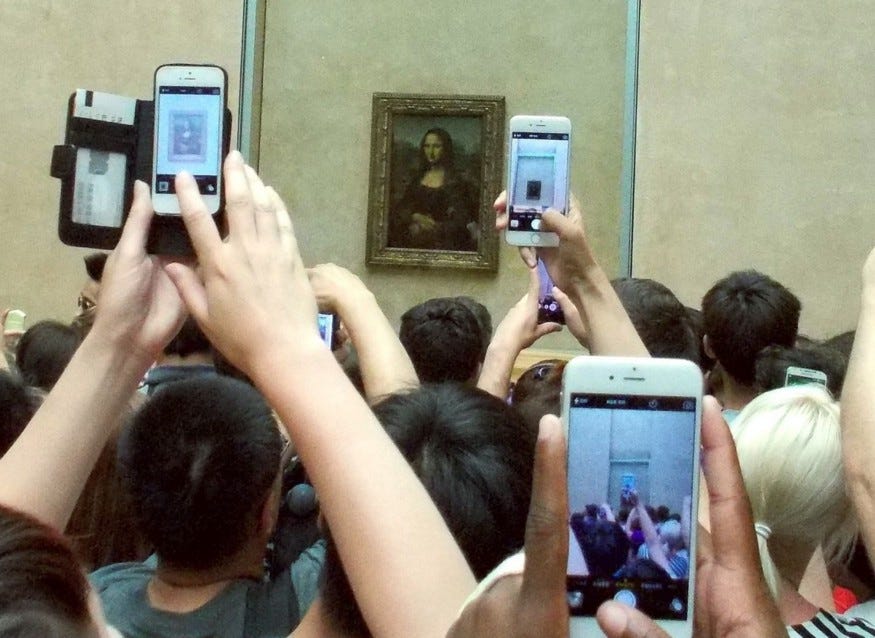

Last winter, as I was road-tripping through the Great Smoky Mountains with my dad and brother, we drove past a roadside gift shop that had an overlook with a sign that proclaimed “Most-photographed view in the Smokies.” And I thought: “Why would anyone take a picture of the most-photographed view? To get a photo that would look the exact same as a bunch of other people’s?”

It did not say it was the widest or most scenic or most picturesque view in the Smokies. No. The “most-photographed.”

This made me think about all the travel photos that way too many people post. You know how everyone posts a picture of the airplane wing on their Instagram stories when they go on a flight? Or how there is some kind of gene that compels people to pretend to support the Leaning Tower of Pisa when they visit it. Or the St. Louis equivalent: pretending to hold up the Arch. And then there’s imitating the Abbey Road cover in London or posing like the characters from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off at Whatever Art Museum That Is In Chicago No I Won’t Look It Up You Know The One.

On that same road trip, we visited Ruby Falls Cave in Lookout Mountain next to Chattanooga, Tennessee. It’s a bit of a cheesy place to visit, with its crowded gift shop selling pick-your-name keychains, with its acne-faced guides shuttling babbling crowds through family-friendly cave tours.2 But I am grateful that I went there, because I left the experience pondering the cave’s history.

So, Ruby Falls Cave was not naturally connected to the surface in any way. It was hidden until 1928, when a geologist named Leo Lambert drilled down to it — by accident. You see, there was another cave on Lookout Mountain, called Lookout Mountain Cave, that had been closed off to build a railroad tunnel. Lambert bought some land on the mountain to drill down and create a new entrance.

But before he hit Lookout Mountain Cave, he struck an opening 18 inches tall and four feet wide. He crawled through this crack for 17 hours. For most of its length, it remained cramped. As the cave widened, he discovered a gallery of rock formations and the 145-foot Ruby Falls.

Imagine what it would have been like to crawl through a narrow, black, rocky passageway for hours, not knowing what you would find, and then to shine your lamp into the darkness and see things no human had seen before. To discover a space unknown to the outside world.

That idea stands in stark contrast to the “most-photographed view” and the airplane wing photos and the Ferris Bueller photos. How rarely do any of us do things that haven’t been replicated by thousands of other people? In this world of billions, does a person who wants to do anything but repeat the actions of other members of the crowd have to literally crack the earth’s surface? Mine for it like it were some kind of scarce mineral?

Traveling is becoming (or has become, or has always largely been) an act of imitation, not exploration.

It is true that even if millions of people flock to the same place, their experiences will not be identical. Their memories will always have slight differences due to their individual tastes and values, what they focused on, the weather, etc.

But it is also true that people are not even seeking individual experiences, they are seeking the experiences that other people have. There’s something wrong when people don’t even independently think about what kind of experiences they want based on their own values, and simply flow with the tide of popular opinion. Does a person even have his own identity at a point when he does not think about whether he finds a landscape beautiful and merely accepts that it must be, because after all, it is the most-photographed view

I am not immune from this. I have taken that photo of the wing before. And on the road trip I just got back from—to Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa3—I stopped at a cheese shop as soon as I crossed into Wisconsin because, well, you have to buy cheese in Wisconsin, right?4

There were several times on my trip where I felt I should visit a certain site. Not “wanted to.” “Should.”

In Springfield, IL, I had a cup of chili solely because the city calls itself the “Chilli [sic] capital of the civilized world” (for some reason). The Minnesota State Fair was going on while I was in the Twin Cities, and—though I ultimately decided I had better things to do—I did experience that nagging feeling that I “should” visit. That might have been interesting though. I hear they had life-size butter sculptures.

Another reason exploration has become an endangered species is because many people choose travel experiences that are in every sense planned, packaged, boiled down to a routine — whether by the tourists themselves or by some cruise line or resort. We are settling for travel-by-numbers, adventures that consist of completing a checklist, sometimes literally. Planning things out is not an eldritch evil: It can simply be a way to make sure you use your time well. Planes and trains and PTO must all happen on schedule. But shrink-wrapped travel can also eliminate room for exploration. I’m thankful that I don’t have experience with the most restricted forms of it.

But wait: I sound very anti-technology and anti-society. Humans have built this world in which we have Google Maps to tell us where to go, websites to suggest the best places to visit, caves that have been made safe so a stalactite does not fall and gore us, running water, no one trying to kill us, etc. — and I’m rejecting it because it’s not exciting enough?

You might respond that I can complain about certain things without discarding the idea that technology and a cohesive society are good in general. It is just an exception, right? But this falls flat.

The “principle” that “civilization = good” stops being much of a principle if there are a zillion asterisks that are worth caring about. How do I coherently understand and explain why it seems bad in certain ways while being good in others?

If a bit less civilization than we have now would actually be good, why not a bit less than that… and a bit less than that? How do we know when to stop?

I will resist recounting the horrors of centuries past, or tales of people who have escaped from North Korea or emigrated from the third world today — it will suffice to say that if modern civilization collapses into chaos, it will unleash unimaginable suffering. Therefore, it is destructive to nitpick everything. Though flawed, the stability and abundance that we in the 21st-century developed world experience is rare throughout history. Human society is a complex system that none of us can comprehend in full, and tampering could have unpredictable effects, much like introducing an invasive species into an ecosystem.

Also, it would cause people to lose confidence that civilization is actually a good thing. Any downsides must be shrugged off as “That’s how civilization works” unless I have either a better alternative or an explanation of how civilization is good if I am always criticizing it.

Can anyone tell me why a world in which you get your beating heart ripped out by a witch doctor is superior to one in which you eat nutrient cubes and sit on the couch playing Candy Crush and watching Cars 12? I can’t.

There is no one stopping me from returning to barbarism if I want to. I can go to Cameroon and live in the jungle. The monkeys might kill me, but no humans will stop me from going.

What do I want to do, wander around random places with no planning or information? If that’s my ideal travel experience, I’m more than welcome to do it. There’s a chance that I might stumble upon something moderately interesting, but it’s equally likely that I will get stabbed.

Why not wander around in the wilderness with no map or compass or anything to tell me where to go? It would certainly be unpredictable.

In all sincerity, it is hard to overestimate the convenience of immediate access to the quickest route to any place, reviews of the best (and worst) restaurants, reliable and cheap lodging through Airbnb, etc. Without them, trips would have a lot more snags.

Maybe the past had more things left to discover, but that unpredictability was not always a good thing. The scraps of shipwrecks on [redacted] Island serve as potent reminders of this reality. There’s a reason the Door Peninsula got its name: It’s because sailing around it was like being on death’s door.

And as for my obsession with “unique” experiences: I should keep in mind that just because something is sincere or original, that does not mean it is good. Likewise, just because something is the product of social norms, that does not mean it is bad.5

The point is, a lot of life is imitation, and that’s not a bad thing. If we each created our understanding of the world from scratch, it would be overwhelming and defeat the point of us having language and culture to pass on information. If a lot of people like to visit a certain place, that might be a sign that it’s worth visiting. It’s useful to have indications of quality.

But we have entered into a phenomenon where we visit places simply because they are popular. It’s like the existence of celebrities that are famous just for being famous (Think Kylie Jenner). Many tourists are not following social signals out of a belief that they are pointing towards valuable experiences, but simply out of a desire to visit places that are well-known for the sake of it.

There was a bookshop on [redacted] Island, and it sold a book about navigation. The blurb on the jacket mentioned something about how Google Maps is destroying our sense of direction, and how we’re losing out on the experience of navigating as a whole. I did not buy it, because the appearance of fate is not enough to make me impulsively chuck $20 at a book.6 But it made me think about the idea.

When I stopped for lunch in Springfield, my phone almost died, and I didn’t have a working car charger. As my battery drained to zero, I scrawled my directions on the first paper I grabbed: a cereal box. From there, I navigated up to Wisconsin, not quite by the stars or the sun, but with a bit more effort than Google telling me exactly where to turn. By this slightly more old-school navigation, I had to pay attention to the highway numbers to make sure I hadn’t run miles off-course. If I missed a single turn, I would be hopelessly lost unless I found a phone charger. None of those things happened, but I can’t say I would do it again.

However, there is something to the idea that Google Maps promotes the non-use of human faculties. I hate to be Mr. “Phone Bad,” but it can’t be good to have so much of our mental processing done for us, between auto-correct and Grammarly and this, that, and the other. For places to which I could reasonably navigate without Google, it might be good to find my way there, instead of performing its commands thoughtlessly.

But how can it be good for us to have less knowledge at our disposal?

It’s something like what Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff talked about in The Coddling of the American Mind (2018). People aren’t allowed to take risks and figure things out for themselves anymore, because we have a culture that’s increasingly focused on safety, especially for children. Parents allow children less time to play independently,7 and we’re increasingly told that every challenge is a threat, both in childhood and on into adulthood. But humans need challenges to grow, or our minds weaken like an astronaut’s muscles in zero-gravity. Trial and error is the only way that we learn to adapt to obstacles. You do not learn to drive a car by reading the owner’s manual.

Or, it’s like what the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer talked about when he said that childhood is the best stage of life because it’s when “The intellect […] explores the whole world of its surroundings in its constant search for nutriment: It is then that existence is in itself an ever fresh delight, and all things sparkle with the charm of novelty.”8

I teeter close to the indulgent sentimentality that would make me want to vomit if someone else effused it. But I say this with a straight face and clear eyes. These are simply facts. As far as I can tell from my experience and from what I have read, people need to be able to exercise their mental faculties in order to flourish. We recognize that bears in the zoo need to have toys to play with in order to be healthy, but we think human beings must be content with Cars 12?

Our minds are how we survive, both individually and collectively. We cannot hope to have a functional society if we do not exercise our minds and allow them to wither.

An eagle survives by being able to swoop down from the air and catch mice with its claws. Humans survive by using their minds.

Therefore, if we are in a situation where we are not allowed to exercise our minds, it will be like if an eagle has its claws filed off, or if it is kept in captivity and does not develop its knowledge of how to hunt. If we do not have strong minds, we will not be able to solve problems or keep society running.

All that I said before is true about how we should not hate civilization. But we have to value human mental flourishing and recognize that it requires the preservation of some challenges and unpredictability in our lives.

Exploring new places is a great way to do that.

How to accomplish this without undermining social cohesion is a difficult question that requires more discussion, but it is one that is necessary to answer.

I realize that this whole essay about exploration is about my journey to the exotic land of (checks notes) Minnesota. You may imply that I have not been outside the United States. You may say that if I am to have any authority on this subject, I should go abroad and see things that most Americans probably have not seen. And I agree.9

I would like to go to China and Antarctica, and I would like to go to some caves. Not like Ruby Falls, but ones where you have to crawl. I think caves are one of the few places where you can see things that a truly small number of people have seen.

I worry my desire to travel will make me insufficiently thrifty and workaholic, and if I indulge it too much, doom shall fall on me like a swift ax. I’m already going to visit some friends in New England this month. But I have plans. I would like to. Soon.

What do you think? How do we allow people to have spontaneous experiences without society collapsing? Is it possible? Am I being an idealistic child? What is the Kylie Jenner of travel destinations? I would suggest the St. Louis Arch.

Maybe I will still write that article. If I can’t ruin other people’s travel experiences to make a few bucks, is this even a free country? You can find this all on Google anyway.

If you’re from St. Louis, it’s a bit like Meramec Caverns, although more developed as a tourist destination, and it has a castle on top. If you ever want to know whether some place is a tourist trap, find out if there is a zip line. Apparently someone figured out that’s a great way to engage tourists. That and goats on the roof. Not at Ruby Falls, I mean, but there’s a restaurant in Wisconsin that has goats grazing on a grass roof, and I’ve seen two goats-on-the-roof restaurants in northern Georgia and one in Pigeon Forge, TN. Seinfeld voice: What’s the deal with goats on the roof???

although I didn’t do anything in Iowa except eat at Jimmy John’s and about run out of gas

In my defense, it was right next to the gas station, and I had to get gas because I ain’t paying no Illinois gas tax, O.K.?

I have edited out a sentence that is so buffoonish that I don’t know how I wrote it as a grown adult. I guess I was feeling very #random and “spontaneous” when I originally published this article.

A nice cover, intriguing concept, and well-written beginning, on the other hand…

For example: “The study that offers the clearest picture of the relevant trends was carried out in 1981 by sociologists at the University of Michigan, who asked parents of children under thirteen to keep detailed records of how their kids spent their time on several randomly chosen days. They repeated the study in 1997, and found that time spent in any kind of play went down 16% overall, and much of the play had shifted to indoor activities, often involving a computer and no other children (Hofferth & Sandberg, 2001). This kind of play does not build physical strength and is not as effective at building psychological resilience or social competence, so the drop in real, healthy sociable play was much greater than 16%. […] [Psychologist Dr. Jean Twenge’s] analysis of iGen, the current generation of kids, shows that the drop in free play has accelerated. Compared with Milennials, iGen spends less time going out with friends, more time interacting with parents, and much more time interacting with screens […]” (p. 184–5)

“Counsels and Maxims” (1851)

This is despite the fact that many people who travel to Mexico or France do things that are just as touristy as what people do here (except these travelers get to feel superior to the passportless rubes, as they tweet from their rose-gold iPhones and sip Sauvignon Blanc with Gucci purses on their shoulders). I refuse to accept that the act of passing through customs automatically makes someone more cultured. When these self-appointed cosmopolitans place themselves on gusty heights above those who have never exited their homeland, they endorse an implicitly nationalist premise: that life on one side of an international border is fundamentally and categorically different from on the other side. This is probably not their intention.