Epistemic Status

This post represents my current speculative thinking. It's based on several hours of reading relevant texts and thinking about them in context, as well as on some prior knowledge as an interested layman, but it needs more research and discussion to become comprehensive. Consider this an attempt to spur dialogue. I welcome feedback.1

April 2025: I no longer agree with significant aspects of this article but am leaving it up with that caveat attached

Introduction

Experts warn that safely developing human-level artificial intelligence poses one of the biggest challenges humanity will face this century — maybe ever. But even if we align superintelligent systems with our values, they could still transform our society — socially, politically, ethically — for better or for worse. It will require significant thought to steer that transformation in a beneficial direction.

One major concern is: Will you still have a job?

Optimists think the job market will adapt to AI like it has for past technological revolutions: New jobs will replace the old ones, and higher productivity will make things cheaper for everyone.

Pessimists worry AI automation will cause mass unemployment with all the wealth concentrating in the hands of a few AI owners. This group argues that this necessitates guaranteed income2 or other wealth transfers to ensure a reasonable living standard for the majority.

Tom Davidson from OpenPhilanthropy put it bluntly, “the human brain is a physical system. There’s nothing magical about it.” If you agree with this premise, it’s logical to assume humans will sooner or later build AI smarter than us at everything. And when that happens, as Davidson explained, “[...] it will no longer be the case that you can produce a higher quality service or product than what an AI could do or a robot could do.”

While some people predict that "caring" jobs will remain,3 AI is different from previous technological revolutions: It threatens to automate almost all human tasks, not just a subset. So, mass unemployment is at least worth worrying about.

That's the premise I'll work with for this article: Superintelligent AI will make human labor obsolete, at least for anything beyond subsistence wages.

My question: In that scenario, in what ways would implementing a guaranteed income policy align or conflict with libertarian values and capitalist economic principles?

The concepts are more compatible than they at first might seem. This analysis also explores why capitalist-libertarians4 might support strategies to reduce existential risk from superintelligence.

Why Ask This?

I find it interesting, but that’s not a good enough reason.

Pushback From Capitalist-Libertarians

Opposition to guaranteed income in the context of AI is acute among capitalist-libertarians for two main reasons:

This group tends to oppose redistributive welfare on practical grounds (e.g. cost, reducing incentives for work) or philosophical grounds (meritocracy, property rights).5

They’re also often skeptical that automation will cause mass unemployment, operating on a presumption that technology and the market produce beneficial outcomes.

Two specific benefits to responding to these concerns:

Finding Common Ground

Looking at guaranteed income through its opponents’ lenses could uncover justifications that appeal to their own values. Or we might identify ways to tweak the policy to make it more mutually agreeable.

While libertarians may be a minority, justifications applying to them may also convince others, helping create broad appeal.

Preserving Freedom

AI itself, and policies aiming to regulate it and its consequences, could threaten individual liberty if we're not careful.

For example, researchers at the Centre for the Governance of AI admitted that, “Intrusive compute governance measures risk infringing on civil liberties, propping up the powerful, and entrenching authoritarian regimes,” and that “Centralising the control of [computing power] could pose significant risks of abuse of power by regulators, governments, and companies.”

Currently, many libertarians deny that AI is a threat to address. While it is worth questioning premises, this does not help answer what to do if they are true. Thoughtful input on how to preserve civil liberties is needed. Analyzing guaranteed income (and other AI-related challenges) in libertarian terms could motivate more good-faith conversation from that philosophical quadrant. This, in turn, would ensure that debates about AI policy consider concerns about civil liberties. To the extent that you believe individual freedom is valuable instrumentally or for its own sake, this would be a benefit.

As blogger Zvi Mowshowitz wrote when criticizing libertarian objections to an AI governance bill:

“We need people who will warn us when bills are unconstitutional, unworkable, unreasonable or simply deeply unwise, and who are well calibrated in their judgment and their speech on these questions. [...] Unfortunately, we do not have that.”

Is Philosophy Relevant?

You might think the disagreement is just an empirical question — i.e. will AI cause mass unemployment or not? But at least for some people, empirical views are influenced by philosophical leanings.

If all the solutions you see go against your philosophy, you'll be inclined to deny hat those solutions might be needed. But if I can show how guaranteed income policies could align with your values, maybe you'll be more open to it, at least marginally.6

In a pluralistic society, we need to consider diverse viewpoints on policies to understand potential downsides or improvements and to generate broad appeal.

Capitalism defined

First, let's consider the perspective that views capitalism as good on the consequentialist grounds of economic prosperity, and that, for this reason, holds a strong presumption towards free markets. I will call this perspective neoliberal, to use a more contemporary term, or classical liberal, in a more historical sense. Because this perspective focuses on markets as an instrument for increasing material wealth, neoliberals allow certain “asterisks.”

Definitions of capitalism vary, but common traits include:

Private ownership of means of production. In countries that provide a safety net today, the means of production are still, broadly speaking, privately owned. That is, private entities and not the government own the resources used to make goods and services. Guaranteed income would not have to change this.

Competitive Markets. If we had guaranteed income, McDonald's and Burger King would still compete to get consumers to buy their burgers.

Price System. Supply and demand would still determine their prices.

Profit motive. And their reason for competing would still be to make a profit.

Yes, tax-funded guaranteed income would be an infringement on capitalism,7 but it does not abolish the system's fundamentals. The question is whether it is an appropriate "asterisk" to attach to capitalism from a classical liberal standpoint.

Classical Liberal Support for Redistribution

Interestingly, some influential capitalist thinkers have hinted at supporting a guaranteed income.

Well-Being of the Poor

In The Road to Serfdom, the Austrian School economist F.A. Hayek, who influenced neoliberal thought, wrote that ensuring a "minimum of sustenance for all" is "an indispensable condition of real liberty" because economic security was necessary for individuals to develop “[i]ndependence of mind” and “strength of character.” He suggested that in wealthy societies, the state could guarantee a basic income without “endangering general freedom.”8

This statement from Hayek implies a kind of positive liberty or “freedom from” economic insecurity as a real and desirable aspect of autonomy.

In a 1977 interview, then-Conservative Party leader Margaret Thatcher acknowledged the need for a "certain amount of redistribution" to prevent vast gaps between wealth and poverty: “We would accept a moral commitment [...] that jointly we do try to guarantee some basic standard of life and indeed rather more than a basic standard of life.”9 While she didn't advocate universal basic income, her statement implies that redistribution would be acceptable if the free market failed to provide sufficient living standards.

The point, to be clear, is not that either of these people had no problems with wealth transfers — they did. The point is that, under the worldviews they expressed, the government helping people in dire need was an acceptable “asterisk” to put on the free market, at least in the right situations.

Milton Friedman

Positive Externalities

In Capitalism and Freedom (1962), Chicago School economist Milton Friedman argued that welfare helps not just recipients, but the whole community because “I am distressed by the sight of poverty; I am benefited by its alleviation [...]” He considered this benefit a public good, i.e. a good from which anyone can benefit without reducing availability and for which there is no way to restrict access.

He said although private charity is “in many ways the most desirable” way to alleviate poverty, public goods are subject to the free-rider problem, so the government should provide a minimum income:

[...] I am benefited equally whether I or someone else pays for its alleviation; the benefits of other people’s charity therefore partly accrue to me. To put it differently, we might all of us be willing to contribute to the relief of poverty, provided everyone else did. We might not be willing to contribute to the same amount without such assurance.10

Another suggested public benefit of reducing poverty is less crime.11 Although the evidence on this is unclear,12 reducing crime is an intuitively stronger public good justification than personally not liking to see poverty.

Efficiency

Friedman proposed a Negative Income Tax as a form of guaranteed income, with the goals of cutting administrative costs, reducing negative incentives, and giving recipients more freedom over spending compared to other welfare programs.13

But he made clear in his 1980 book Free to Choose that while NIT was preferable to the existing system, he opposed state welfare.14

Although other capitalist thinkers have advocated for UBI as something that is good in its own right, citing Friedman provides only weak support for broader UBI.15

Objections Invalid: Post-Scarcity

Most of the objections to guaranteed income, or welfare generally, are things that would make sense to worry about in a world where it’s necessary for people to work in order to produce goods.

But if we’re talking about a future where AI can do everything for us and create everything we want, it may no longer economically matter if guaranteed income would require too much government spending or reduce incentives to work. While some types of work may remain desirable, these objections would at least be less significant than today.

For example, Sam Altman estimated that within 10 years, economic growth could be enough that a 2.5% tax on companies and land could fund a $13,500 annual basic income per person — and the payout "could be much higher if AI accelerates growth." Many people who think a lot about AI, such as Davidson and philosopher Nick Bostrom, expect an extreme accelleration.

It is worth noting that many economists disagree, noting that hype about economic transformations is often overstated.

It is hard for me to sit here in 2024 and claim to know what exactly life will look like on the other side of a technological singularity. We will have to figure it out when we get there. But it is plausible that the normal macroeconomic rules may no longer apply. The creation of artificial minds is an unprecedented event.

However, objections based on individual rights and other philosophical grounds would still remain valid even in a post-scarcity world.

Examining Guaranteed Income Through the Lens of Rights

Now, let’s shift from the perspective of valuing economic prosperity in a consequentialist sense to looking at individual rights as a deontological end in themselves.

The Non-Aggression Principle

A core tenet of capitalist-libertarian philosophy is the non-aggression principle developed by Murray Rothbard: “[…] no man or group of men may aggress against the person or property of anyone else.”16 This derives from John Locke's idea that “being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty or possessions.”

Under the NAP, only aggression or threats justify violence in response. This necessitates anarchism, as the state requires force to exist. In an anarchist society, the NAP would describe when individuals or groups should use force to enforce rights.

However, the NAP views rights only in a negative context: absence of coercion, not rights to specific goods. Unemployment or inequality do not count as aggression as people lack a positive right to income in Rothbard’s view. Under this reasoning, using force to fund a guaranteed income policy is not justifiable.

Scope of NAP

Even so, the NAP only limits the use of force — it doesn't cover all moral questions.17 The flip side of its narrow definition of "aggression" means many other tactics — like boycotts, charity, cooperation, and social pressures — are still allowed as methods of social influence.

Guaranteed Income as compensation for AI Risk?

But could there be a justification for (coercively funded) guaranteed income even under the NAP?

Locke believed that victims of criminal harm deserve restitution.18 Libertarian thinkers carried on this belief.19 The development of superintelligence creates a risk of human extinction (which would be a massive violation of property rights)! Therefore, could existential risk (or other harm) created by developing superintelligence justify guaranteed income as compensation?

I’m not the first person to come up with this idea. Robert Miles mentioned it offhand as an argument for why everyone deserves to share in the benefits of AI.20 Similarly, the president of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, Nate Soares, suggested an "apocalypse insurance" policy to transfer money from AI labs to the public if the labs don't reduce existential risk.21

Does AI Risk Count as Aggression Under the NAP?

Short answer: no. Long answer:22

The key question is: Does creating a risk of harm count as "aggression"? If an actual harm has to occur, then in the case of x-risk, it’s too little, too late, as they say.

Nuclear weapons are an example that cuts in favor of the idea that x-risk violates the NAP. Rothbard condemned ownership of nukes because they could not (in most circumstances) be “pinpointed” against aggressors.

“[T]he use of nuclear or similar weapons, or the threat thereof, is a crime against humanity for which there can be no justification,” he concluded. “[...] Therefore, their very existence must be condemned, and nuclear disarmament becomes a good to be pursued for its own sake.”23

You could use similar reasoning about superintelligence: If its damages can’t be controlled, its existence is inherently aggressive.

However, it’s unclear how he jumped from condemning use or threat of use of these weapons to condemning their existence.24 This is a critical distinction when it comes to whether risk is aggression.

In any case, Rothbard elsewhere made clear that:

lt is important to insist [...] that the threat of aggression be palpable, immediate, and direct; in short, that it be embodied in the initiation of an overt act. [...] Once we bring in "threats" to person and property that are vague and future — i.e., are not overt and immediate — then all manner of tyranny becomes excusable.25

It is unlikely that developing AI — even with dangerous capabilities — meets this definition of aggression.26

Broader Definitions of Harm

The NAP’s narrow scope of “palpable, immediate, and direct,” aggression precludes a right to a guaranteed income as compensation. But are there broader conceptions of "harm" that would not?

The Harm Principle

The philosopher J.S. Mill articulated the Harm Principle: “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”27

This contrasts with the NAP, as this passage on the Cato Institute’s Libertarianism.org explains:

Despite their similarity, the two principles are arguably not equivalent. First, harm seems to be a broader concept than aggression: outcompeting an economic or romantic rival is not aggression, but might count as harm. Second, Mill’s principle does not specify that the person to be coerced in order to prevent harm must be the author of the harm to be prevented.

Examples of harm that Mill listed include “unfair or ungenerous use of advantages over [others]” and “selfish abstinence from defending them against injury.” (Using superintelligence to hog up all the wealth could fit this definition, justifying redistributive policies under Mill's principle.)

Externalities

More broadly, some libertarians consider the economic concept of "negative externalities" — costs your actions impose on others — to be a type of harm requiring correction or compensation.28

Ambiguities abound when it comes to whether increasing x-risk falls under these definitions, but the most basic moral instinct suggests that gambling with the destruction of humanity and its light-cone is a violation of the rights of each member of humanity.29 Conceivably, the people doing that owe the rest of us some money.

Practical Limitations

Even if we consider AI risk to be a form of rights-violating "harm," guaranteed income as restitution may not work:

Olivia J. Erdélyi and Gábor Erdélyi pointed out that harms from AI are not “foreseeable” in a legal sense, which is generally a requirement for liability. The authors cited examples of unpredicted AI failure modes as evidence of unforeseeability.30

Also, their paper focused on harms from existing AI (e.g. autonomous vehicles). What is implicit is that liability only applies to harms that have already happened, not to potential harms. So, it would not be relevant for x-risk from superintelligence. (I am not a lawyer.)

Finally, under this reasoning, if those developing AI did so in a way that minimized risk, the grounds for compensation would be legally null. So, such a proposal could enforce AI safety or create a guaranteed income, but not both.

Other Moral Arguments

In their paper “Atlas Nods: The Libertarian Case for a Basic Income,” Miranda Perry Fleischer and Daniel Hemel described a few libertarian-friendly arguments for guaranteed income that stem from moral philosophy, although not in an AI context. I’ll summarize four key arguments below.

The Freezing Hiker

The philosopher Eric Mack proposed the thought experiment of a hiker, who, through no fault of his own, gets lost in the woods and is about to freeze to death. Is the hiker morally permitted to break into an empty cabin (violating property rights) to avoid dying?

Mack argued that to answer “no” would deny the premise of rights that libertarian philosopher Robert Nozick articulated: the individual value of each human life.

Mack wrote, "no moral theory that builds upon the separate value of each person's life and well-being can hold that Freezing Hiker is morally bound to grin and bear it."

Mack used this to argue for redistributive taxation as a means of providing for people who have no other way to survive.

In a world where automation pushes humans out of the job market, are we all thrust into the position of the freezing hiker? Mack mentions three criteria for freezing-hiker-ness:

The hiker must be “faultless.” This would apply in the automation context, unless “fault” includes “did not buy AI stock pre-singularity or find one of the jobs that might hypothetically remain.” This seems unreasonable.

The hiker must be in extreme need. This would apply unless there are other means of income.

The freezing hiker should compensate the cabin owner. In a post-labor economy, it is not clear that this is possible if there is no valuable work for humans to do.31

Injustice in Acquisition

Another argument hinges on the idea that the existing wealth distribution is unjust due to historical coercion. If my ancestor stole from yours and passed the loot onto me, I have something I don’t deserve and should give it back to you.

Nozick argued that the state should redistribute ill-gotten resources back to the descendants of the original owners. However, since doing this precisely would be complicated, Nozick suggested that redistributive taxation could serve as a "rough rule of thumb" for correcting these injustices.32

The Lockean Proviso

There’s another thing Locke said called the Lockean Proviso. It states that an individual has the right to claim natural resources “at least where there is enough, and as good, left in common for others.”

Locke’s theory of property revolved around mixing your labor with unused land, such as by turning it into a farm, which then made that land your property. But if this acquisition doesn’t fulfill the proviso, it may be illegitimate, therefore requiring rectification. Fleischer and Hemel noted it is unclear what Locke meant by “enough, and as good,” but they suggested three interpretations that could justify a social safety net:

“[...]others cannot be made ‘worse off’ in some sense by an appropriation or use,” for it to be moral. The authors argue that when people can't access the labor market to earn sustenance, this proviso is violated.

The proviso is satisfied if all individuals have access to basic needs.

“[...]private appropriation of resources leaves others at least as well off if and only if such others—thinking rationally and looking out for their own interests—would not choose to prevent such appropriative acts from occurring.”

Guaranteed income would be justified if you believe in the first or second framework. Under the third framework, superintelligence pushing everyone out of work would itself be a situation that the populace “would choose to prevent.”33

The Social Contract

Similarly, those who believe a social contract theory justifies the state's existence emphasize implicit consent of the governed. (After all, you never get a literal chance to sign a social contract.) For example, Robert Epstein conceived of the state as a “network of forced hypothetical exchanges” i.e. the state must be such that all citizens would agree if they had a chance. Fleischer and Hemel argue that at least some redistribution is necessary for the worst-off members of society to rationally consider the social contract legitimate.34

Socially Responsible Capitalism

In addition to the above arguments for a political obligation for redistribution, there's also the idea that the wealthy have a moral obligation to (voluntarily) support their communities and those less fortunate. This idea has existed for a long time — for example, philanthropists like Andrew Carnegie and Robert Brookings during the Gilded Age. Today, supporters of "socially responsible capitalism" like Whole Foods founder John Mackey promote a similar view.

Could such an obligation be justification for a privately-funded guaranteed income?

One way this could work: The Future of Humanity Institute proposed the Windfall Clause: a contract in which companies commit to donating a share of extreme profits from superintelligence. The authors argued companies would be willing to do to this to:

Improve their public image.

Attract, retain, and improve relations with employees who want to work for “socially responsible” firms.

Make it more likely that governments view them favorably.35

Without delving into pros and cons, a voluntarily funded guaranteed income is at least plausible and perhaps preferable to a tax-funded version. Practical advantages could include lower overhead costs, not being limited by national borders, less concentration of government power, and avoiding political conflicts over how to implement it. Downsides? Maybe companies don't contribute enough money. But then again, there's no guarantee the government would properly fund and maintain a guaranteed income either.

Ambiguity

There are many counterarguments to the justifications I’ve laid out — but for brevity's sake, I'll detail one issue that is particularly important.

If we’re talking about negative externalities, who has any idea what is the limit to what harms or risks are acceptable to create? If you live in civilization, you can expect that any action you take will impact others, at least slightly.36

For example, Mill’s harm principle is frustratingly vague. Mill defined harmful conduct as that which “affects prejudicially” other people’s “rights” to security and autonomy “directly, and in the first instance”

... whatever that means.

If a reporter publishes facts about a corrupt businessman or politician, this reputational damage would reduce the exposé subject’s freedom of action. But it is unclear that this makes such publication immoral.

If an AI developer's work increases x-risk, is that a sufficiently "direct" harm to fall under the Harm Principle? You could argue both ways.

Similarly, regarding Friedman's view that his “distress” about seeing poverty makes reducing it a "public good": If such a subjective and vague justification counts, is there anything on which you can’t slap that label — public good?37

Regardless of your political philosophy, it is clear there must be some limiting principle or criterion for deciding what harms are punishable. Otherwise, it opens the door to rationalizing any coercive policy by fabricating some subjective "harm."

Conclusion

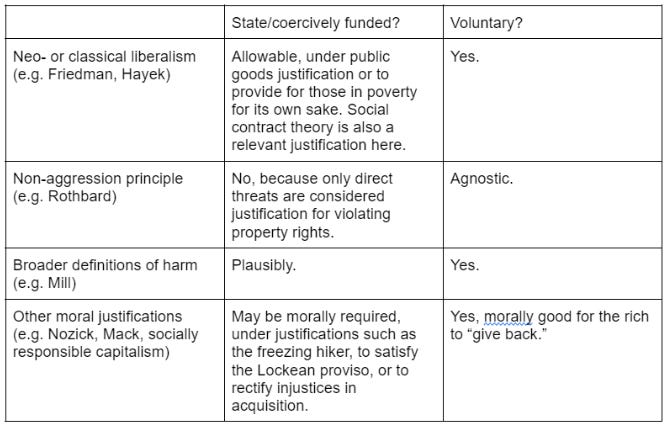

So is a guaranteed income justifiable from a libertarian perspective? Here's a rough chart:

The Freezing Hiker scenario provides the most persuasive / least thin moral argument, libertarianly speaking, because it rests on the value of the individual life. Would you want to be the one insisting the freezing masses respect your cabin's sovereignty as they perish? Unlike arguments from externalities, it does not suffer from practical problems or unbounded definitions of harm/benefit.

Voluntary guaranteed income is also permissible, but this is trivial. The previous paragraph is my take on the more controversial question of whether the state can do it.

As far as economic objections, such as cost and incentives, it's intuitive that a true post-scarcity scenario would nullify them. Economics, as they say, is the allocation of scarce resources. But who knows how AI would impact society? We'd need more modeling to say this with confidence.

Two questions for critics

For critics who say I am not respecting individual rights enough: Are we obligated to starve if AGI renders us all unemployable? Sincere question. Set aside the empirical question of whether this scenario will happen. I hope it doesn’t. But consider it as a thought experiment. I want to preserve rights, but the question is, in what way do they apply here?

To someone on the other side, who is asking “Why do we even need to come up with a justification for not letting the 99% starve?”: What is your theory of rights and how does it prevent arbitrary violations based on any alleged benefit or harm I can contrive?

We all want a maximally good world, but unless we ask this question, we will instead fall into a sand pit of ends-justify-the-means-ism.

Implications

Ensuring economic prosperity is likely a high priority for generating popular support for guaranteed income policies. If we face post-scarcity, these economic concerns become less relevant.

It is plausible that poverty and inequality would become relevant to more people if unemployment threatens to become widespread.

Violations of property rights will likely be unconvincing to most people outside of libertarian circles. Despite this and the aforementioned philosophical and legal limitations, framing guaranteed income as compensating for risk could be persuasive broadly. Governments already regulate nuclear power, weapons, pollution, etc. to mitigate potential harms — so positioning guaranteed income (or AI policy) as an extension of these “normal” functions of the state could make it seem less radical.

Further work

The most ambitious goal on this topic would be to discover a philosophically grounded, clear, and consistent theory of rights and determine whether this allows for guaranteed income. Has someone done this already?

Insofar as empirical predictions about the future (rather than philosophy), remain a barrier to agreement: It is valuable to prove that superintelligence will in fact hang a “humans need not apply” sign on the labor market.38

It is also valuable to model what a post-labor economy might look like and how the transition would occur.

Another question is how and when and in what way would private and government policymakers put a guaranteed income in place? This would seem to depend on your particular justification. E.g. At what point are jobs scarce enough for humans to become Freezing Hikers? If existential risk is a justification for guaranteed income as restitution, how much risk is necessary for this to take effect, and why? How much redistribution is necessary to meet the Lockean proviso or make the social contract justifiable?

Beyond economic prosperity and individual rights, there are other questions to consider:

Models of economic efficiency: What is a consistent model of the world in which capitalism, on the one hand, is a moral economic system that produces good outcomes and, yet, would require redistribution to support most of the population in the instance of AGI?

Centralization of power

Unintended consequences

Just because it is justifiable for a government to adopt a policy, does not mean it would be good.

What does a freedom-preserving guaranteed income policy look like specifically? How do we know it would be effective? How specifically might a private guaranteed income be funded? Other than cash transfers, could there be other ways of protecting both living standards and autonomy (i.e. methods by which ownership or use of AI, or both, might come to be broadly distributed)? What are the pros and cons of such methods?

Finally, it is important to consider the non-economic implications of superintelligence-induced unemployment. Let’s say they throw a guaranteed income at us; will we be happy with that, or bored not having to work?

Acknowledgements: Anastasia Uglova’s project proposal, “UBI, but Make It Capitalist,” for the “AI Safety Fundamentals” course, loosely inspired this article, and some of the research was informed by suggestions for the development of that project, including from Asheem Singh and David Abecassis, but this article was executed under my own auspices. Thank you to BlueDot Impact, facilitators, and community members for making the course happen, which exposed me to fascinating information about AI research, allowed me to make connections with other people who care about AI safety, and inspired me to do further research on AI and on its consequences, including in a more quantitative direction than this article.

Several different terms for proposed policies are relevant; Universal basic income is the most common. Proposals differ in terms of whether payments will be universal or means-tested, how much income will be provided, funding sources, and other factors. I will use “guaranteed income” as a generic name for any policy that transfers wealth through unconditional cash payments to prevent poverty. Differences between proposals are meaningful, but my goal is to analyze the overall concept.

E.g. childcare, eldercare, and teaching. I wonder if this prediction is an inadequate internalization of the idea that AI could eventually simulate anything a human mind can do. Maybe the elderly will want humans to care for them because they value being cared for by a human — or maybe we just think so because AI is not yet able to fully emulate human social skills.

I say “capitalist-libertarian” to distinguish from left-libertarianism, but I will use it interchangeably with “libertarian” for convenience.

This is in spite of the fact that some libertarians consider UBI in particular to be a less bad alternative to the existing system, or even a desirable policy in and of itself, which I’ll discuss later.

This is not an exact parallel, but consider the analogy of people who don’t believe in climate change. Is it more likely that someone decides not to believe in climate change based on assessing facts, or that he does so because he sees other people using climate change to promote policies he disagrees with and motivated reasoning ensues? This is not intended as an unfair comparison. Reasonable people can disagree.

For example, taxes can be considered a decrease in private ownership proportional to tax revenue. Also, even some supporters admit that UBI would create at least some disincentive on productivity, although not necessarily worse than other types of social safety net. See e.g. “Atlas Nods: The Libertarian Case for a Basic Income” by Miranda Perry Fleischer and Daniel Hemel, Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics, p. 1248-1252. As discussed later, this is not necessarily a concern in an AI-specific context.

P. 66-67. It was only when the government tried to protect “the relative position which one person or group enjoys compared with others,” that it went too far, he argued.

She went on to specify that she did not believe the U.K. had high enough inequality to necessitate increased redistribution. She did not state a reasoning for why or when economic inequality is objectionable. Moral justifications for ensuring a minimum standard of living will be discussed in a later section.

Capitalism and Freedom p. 191.

This is a justification that goes back to one of the earliest suggestions of guaranteed income, Thomas More’s Utopia: “it would be far more to the point to provide everyone with some means of livelihood, so that nobody's under the frightful necessity of becoming first a thief, and then a corpse.”

“Atlas Nods” p. 1224-1225

One reason why unconditional cash payments are a more appealing form of welfare from a libertarian perspective is skepticism of the state’s ability to determine who needs money and how much and what they should spend it on. Fleischer and Hemel summarized on “Atlas Nods” p. 1210: “Libertarians — who are generally skeptical of the state’s ability to implement social programs — should be especially skeptical of any claim that the state can distinguish the work-capable from the work-incapable without error. The resulting irony is that a skepticism of state capacity militates in favor of a more expansive state-provided safety net, given the state’s (assumed) incapability of limiting the safety net to the truly work-incapable”

P. 119: “Most of the present welfare programs should never have been enacted. If they had not been, many of the people now dependent on them would have become self-reliant individuals instead of wards of the state. In the short run that might have appeared cruel for some, leaving them no option to low-paying, unattractive work. But in the long run it would have been far more humane. However, given that the welfare programs exist, they cannot simply be abolished overnight.”

Especially since NIT is not “universal” — it would only apply to people below a certain income.

For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto p. 27. Intermediate historical formulations include 19th century American anarchist Benjamin R. Tucker’s principle that “the greatest amount of liberty compatible with equality of liberty; or, in other words, as the belief in every liberty except the liberty to invade” and Ayn Rand’s Principle of Non-Initiation of Force (1946).

See e.g. Ethics of Liberty 152

See also this analysis.

See e.g. For A New Liberty p. 108: “[In a libertarian world] a crucial focus of punishment will be to force the criminal to repay, make restitution to, the victim.”

As far as I can tell, it wasn’t mentioned in the FHI paper his video was about. Also, for an argument for UBI as payment for environmental externalities, see Atlas Nods 1232-1234

This was not specifically a guaranteed income proposal. Soares also suggested non-forcible mechanisms for requiring this insurance, namely a private contract enforced “on pain not of violence but of being unable to trade with civilized people.”

This is not as far-fetched as it may initially seem. The NAP definition is not constrained to blatant examples of force that “aggression” would naturally imply. For example, Rothbard wrote that air pollution constitutes “aggression against the private property of the victims.” (For A New Liberty p. 318-327)

The Ethics of Liberty p. 190-191.

Especially when elsewhere he states that “every man has the absolute right to bear arms — whether for self-defense or any other licit purpose. The crime comes not from bearing arms, but from using them for purposes of threatened or actual invasion.” (The Ethics of Liberty p. 81) A follower of Rothbard, Walter Block, likewise conflated use and ownership of nuclear weapons, (proscribing both) and clarified that the reason this applies to nuclear weapons, but not other things that pose risk of harm, e.g. nuclear power, is because “The difference is that the one is a weapon, the other not.” Block did not state a specific rationale for why this makes a difference, especially given that he mentions that nuclear weapon ownership in cities should be illegal even for nonviolent purposes, e.g. in a museum. If I get blown up because my neighbor had a nuclear something in his basement, it doesn’t matter a whole lot to me whether it was a reactor or a bomb. In any case, AI is not a “weapon” under a reasonable definition, so this bodes poorly for the NAP proscribing it.

The Ethics of Liberty p. 78

One free-market writer wrote that the NAP does not classify any risk of accidental harm as “aggression” unless the risk was imposed by a direct threat of violence.

It is worth noting that Mill was a socialist, but his economic ideas are not as relevant here as his beliefs about rights.

For example, economist Ronald Coase suggested that parties harmed by each other’s activities, e.g. pollution, should negotiate payment to internalize externalities. There are practical caveats,* but I cite this as an example of libertarian recognition of a set of problems justifying compensation that is broader than the NAP.

* 1) This payment could flow in either direction, not necessarily from polluter to victim, contra A.C. Pigou. 2) Coasian bargaining has some well-known limitations around transaction costs and negotiating roadblocks.

And any extraterrestrials in our light-cone, if they have rights.

I’m not certain that this is good. If you can’t foresee whether something will cause harm or not, and you have a strong a priori reason to believe it will, maybe we should have some kind of a precautionary principle where you don’t do that thing by default?

The authors also argue that it is uncertain how courts would handle AI liability, which could reduce innovation. Not obvious whether or not this is bad from an x-risk perspective.

“Atlas Nods” p. 1207-1210, citing Eric Mack, Non-Absolute Rights and Libertarian Taxation, and Robert Nozick, Anarchy, State and Utopia.

“Atlas Nods” 1218, citing Anarchy, State and Utopia

Arguments for wealth redistribution on the grounds of questioning the validity of land appropriation were also expressed by Henry George and Thomas Paine.

“Atlas Nods” p. 1228-1230, citing “Taxation in a Lockean World”

P. 6-7

For example, see this passage Alexander Volokh wrote for Libertarianism.org:

“Some people’s happiness depends on whether they live in a drug-free world, how income is distributed, or whether the Grand Canyon is developed. Given such moral or ideological tastes, any human activity can generate externalities; one may choose to ignore such effects for moral or political reasons, but they are true externalities nonetheless. […] Free expression, for instance, will inevitably offend some, but such offense generally does not justify regulation in the libertarian framework for any of several reasons: because there exists a natural right of free expression, because offense cannot be accurately measured and is easy to falsify, because private bargaining may be more effective inasmuch as such regulation may make government dangerously powerful, and because such regulation may improperly encourage future feelings of offense among citizens.”

See also “Atlas Nods” p. 1226-1228

This is the direction in which Uglova (et al.?)’s project went.